|

Supplementary code for the Build a Large Language Model From Scratch book by Sebastian Raschka Code repository: https://github.com/rasbt/LLMs-from-scratch |

|

Chapter 4: Implementing a GPT model from Scratch To Generate Text#

from importlib.metadata import version

print("matplotlib version:", version("matplotlib"))

print("torch version:", version("torch"))

print("tiktoken version:", version("tiktoken"))

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

PackageNotFoundError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[1], line 3

1 from importlib.metadata import version

----> 3 print("matplotlib version:", version("matplotlib"))

4 print("torch version:", version("torch"))

5 print("tiktoken version:", version("tiktoken"))

File /Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.10/lib/python3.10/importlib/metadata/__init__.py:946, in version(distribution_name)

939 def version(distribution_name):

940 """Get the version string for the named package.

941

942 :param distribution_name: The name of the distribution package to query.

943 :return: The version string for the package as defined in the package's

944 "Version" metadata key.

945 """

--> 946 return distribution(distribution_name).version

File /Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.10/lib/python3.10/importlib/metadata/__init__.py:919, in distribution(distribution_name)

913 def distribution(distribution_name):

914 """Get the ``Distribution`` instance for the named package.

915

916 :param distribution_name: The name of the distribution package as a string.

917 :return: A ``Distribution`` instance (or subclass thereof).

918 """

--> 919 return Distribution.from_name(distribution_name)

File /Library/Frameworks/Python.framework/Versions/3.10/lib/python3.10/importlib/metadata/__init__.py:518, in Distribution.from_name(cls, name)

516 return dist

517 else:

--> 518 raise PackageNotFoundError(name)

PackageNotFoundError: No package metadata was found for matplotlib

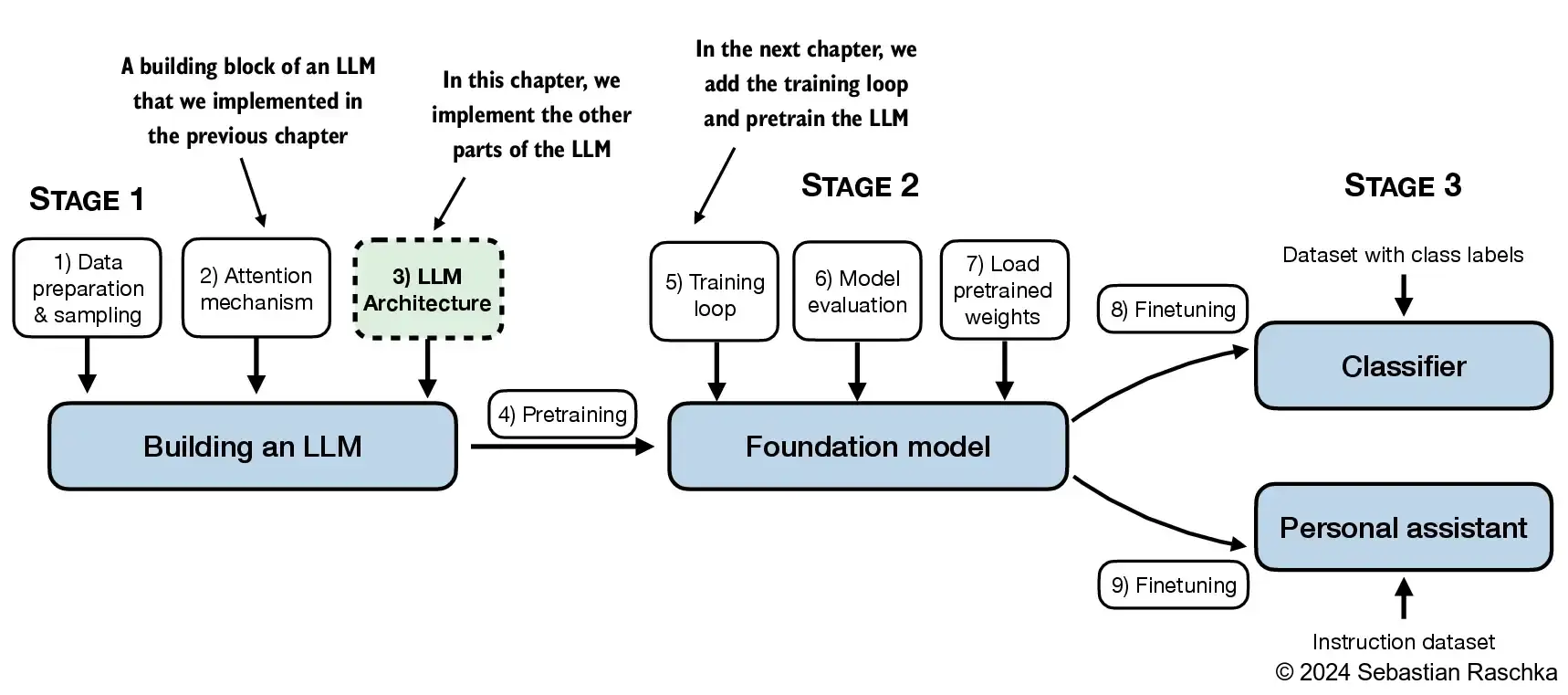

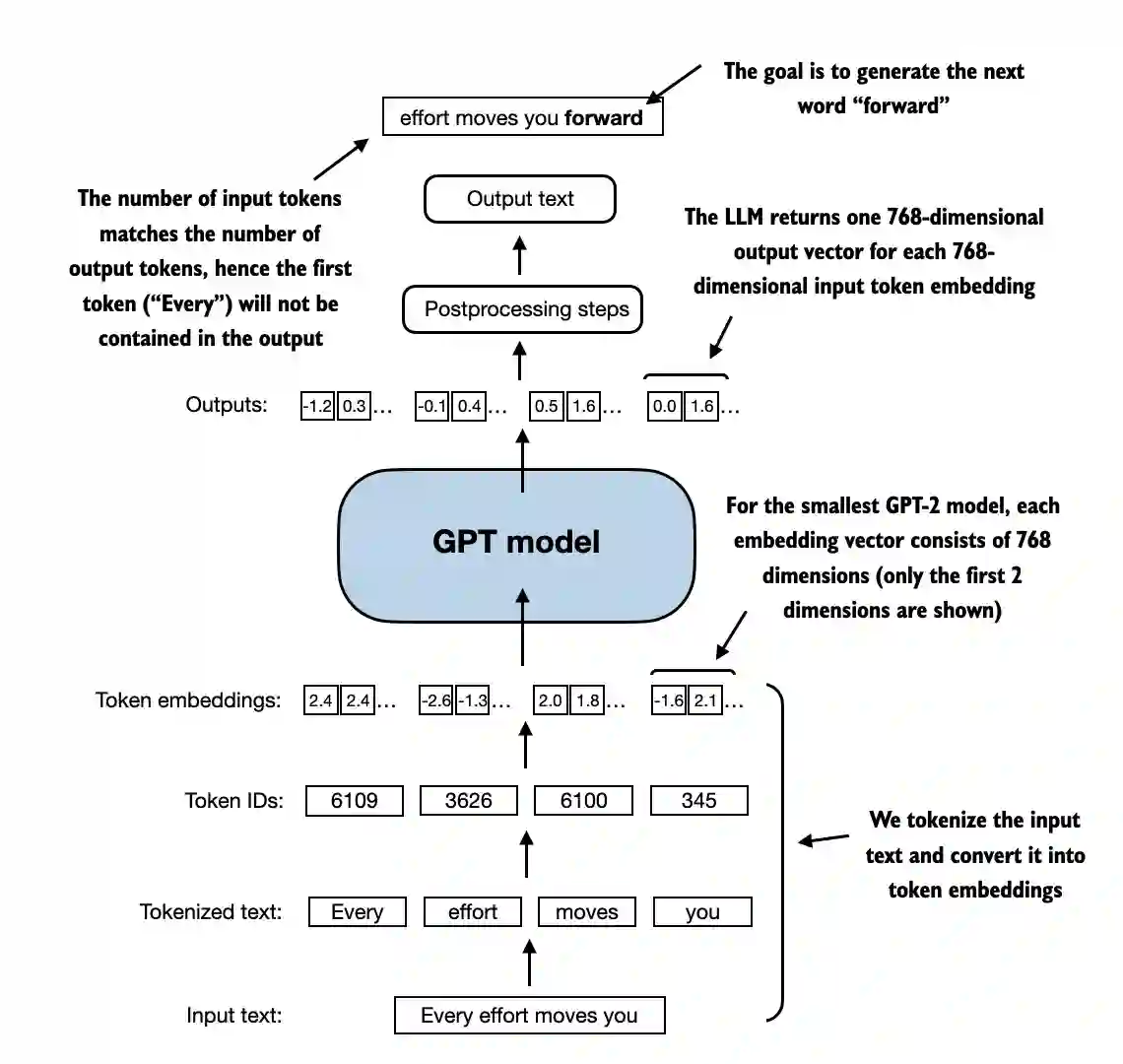

In this chapter, we implement a GPT-like LLM architecture; the next chapter will focus on training this LLM

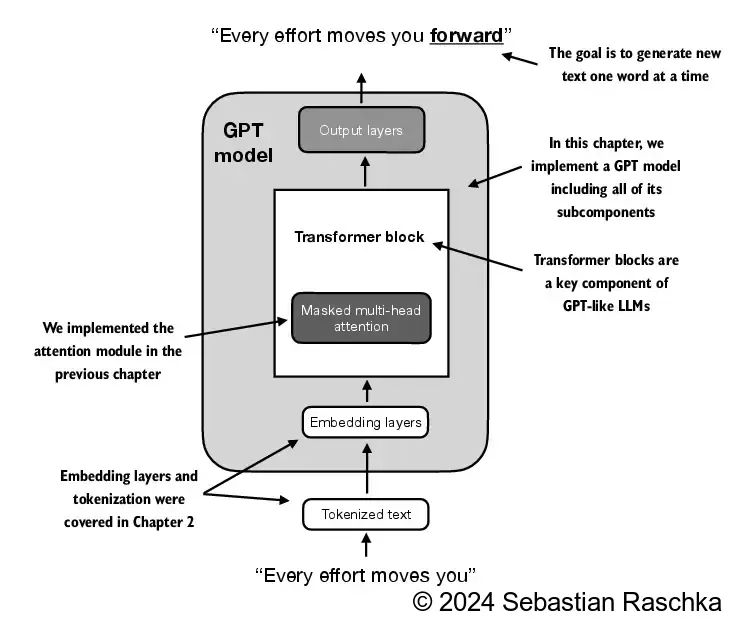

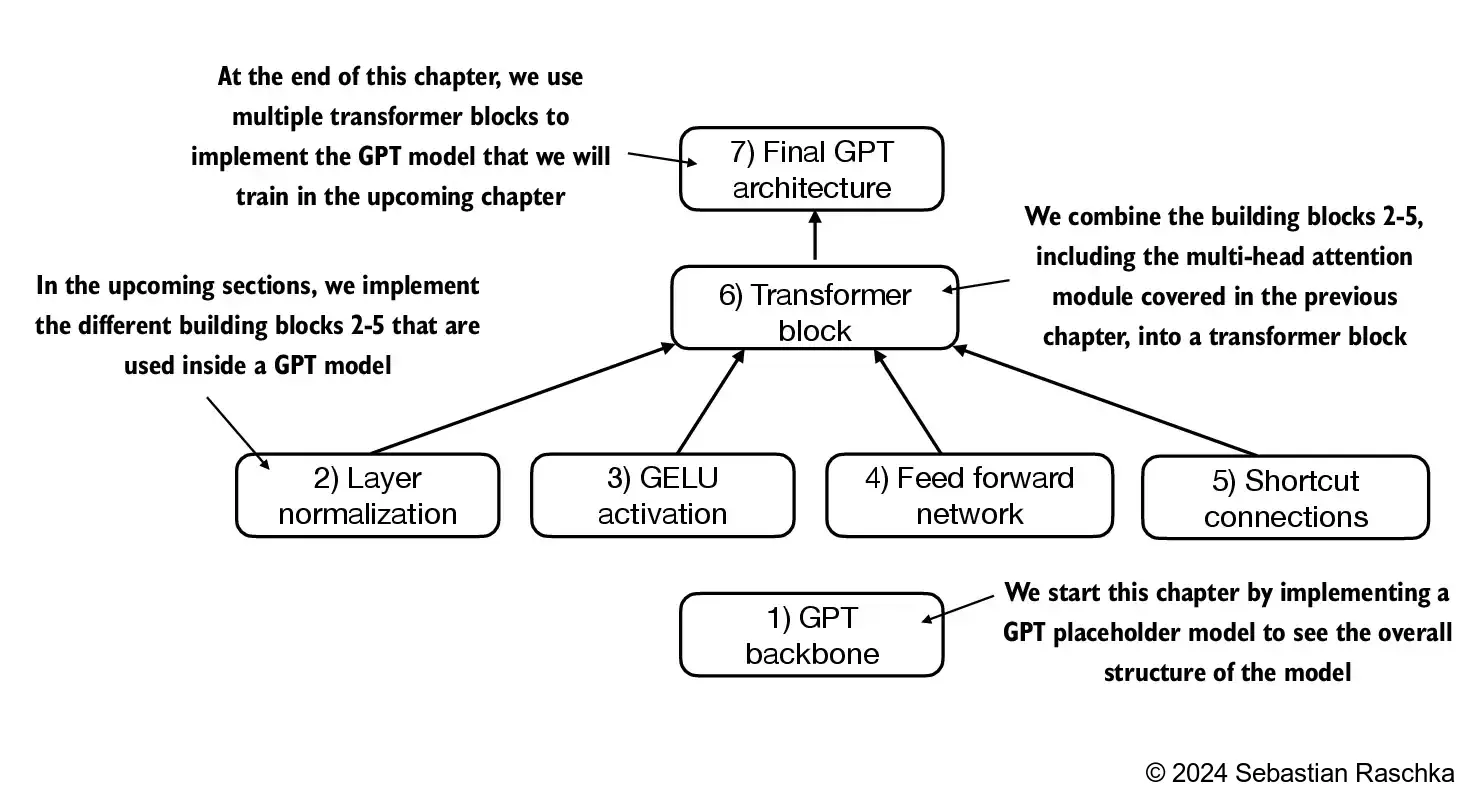

4.1 Coding an LLM architecture#

Chapter 1 discussed models like GPT and Llama, which generate words sequentially and are based on the decoder part of the original transformer architecture

Therefore, these LLMs are often referred to as “decoder-like” LLMs

Compared to conventional deep learning models, LLMs are larger, mainly due to their vast number of parameters, not the amount of code

We’ll see that many elements are repeated in an LLM’s architecture

In previous chapters, we used small embedding dimensions for token inputs and outputs for ease of illustration, ensuring they fit on a single page

In this chapter, we consider embedding and model sizes akin to a small GPT-2 model

We’ll specifically code the architecture of the smallest GPT-2 model (124 million parameters), as outlined in Radford et al.’s Language Models are Unsupervised Multitask Learners (note that the initial report lists it as 117M parameters, but this was later corrected in the model weight repository)

Chapter 6 will show how to load pretrained weights into our implementation, which will be compatible with model sizes of 345, 762, and 1542 million parameters

Configuration details for the 124 million parameter GPT-2 model include:

GPT_CONFIG_124M = {

"vocab_size": 50257, # Vocabulary size

"context_length": 1024, # Context length

"emb_dim": 768, # Embedding dimension

"n_heads": 12, # Number of attention heads

"n_layers": 12, # Number of layers

"drop_rate": 0.1, # Dropout rate

"qkv_bias": False # Query-Key-Value bias

}

We use short variable names to avoid long lines of code later

"vocab_size"indicates a vocabulary size of 50,257 words, supported by the BPE tokenizer discussed in Chapter 2"context_length"represents the model’s maximum input token count, as enabled by positional embeddings covered in Chapter 2"emb_dim"is the embedding size for token inputs, converting each input token into a 768-dimensional vector"n_heads"is the number of attention heads in the multi-head attention mechanism implemented in Chapter 3"n_layers"is the number of transformer blocks within the model, which we’ll implement in upcoming sections"drop_rate"is the dropout mechanism’s intensity, discussed in Chapter 3; 0.1 means dropping 10% of hidden units during training to mitigate overfitting"qkv_bias"decides if theLinearlayers in the multi-head attention mechanism (from Chapter 3) should include a bias vector when computing query (Q), key (K), and value (V) tensors; we’ll disable this option, which is standard practice in modern LLMs; however, we’ll revisit this later when loading pretrained GPT-2 weights from OpenAI into our reimplementation in chapter 5

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

class DummyGPTModel(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, cfg):

super().__init__()

self.tok_emb = nn.Embedding(cfg["vocab_size"], cfg["emb_dim"])

self.pos_emb = nn.Embedding(cfg["context_length"], cfg["emb_dim"])

self.drop_emb = nn.Dropout(cfg["drop_rate"])

# Use a placeholder for TransformerBlock

self.trf_blocks = nn.Sequential(

*[DummyTransformerBlock(cfg) for _ in range(cfg["n_layers"])])

# Use a placeholder for LayerNorm

self.final_norm = DummyLayerNorm(cfg["emb_dim"])

self.out_head = nn.Linear(

cfg["emb_dim"], cfg["vocab_size"], bias=False

)

def forward(self, in_idx):

batch_size, seq_len = in_idx.shape

tok_embeds = self.tok_emb(in_idx)

pos_embeds = self.pos_emb(torch.arange(seq_len, device=in_idx.device))

x = tok_embeds + pos_embeds

x = self.drop_emb(x)

x = self.trf_blocks(x)

x = self.final_norm(x)

logits = self.out_head(x)

return logits

class DummyTransformerBlock(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, cfg):

super().__init__()

# A simple placeholder

def forward(self, x):

# This block does nothing and just returns its input.

return x

class DummyLayerNorm(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, normalized_shape, eps=1e-5):

super().__init__()

# The parameters here are just to mimic the LayerNorm interface.

def forward(self, x):

# This layer does nothing and just returns its input.

return x

import tiktoken

tokenizer = tiktoken.get_encoding("gpt2")

batch = []

txt1 = "Every effort moves you"

txt2 = "Every day holds a"

batch.append(torch.tensor(tokenizer.encode(txt1)))

batch.append(torch.tensor(tokenizer.encode(txt2)))

batch = torch.stack(batch, dim=0)

print(batch)

tensor([[6109, 3626, 6100, 345],

[6109, 1110, 6622, 257]])

torch.manual_seed(123)

model = DummyGPTModel(GPT_CONFIG_124M)

logits = model(batch)

print("Output shape:", logits.shape)

print(logits)

Output shape: torch.Size([2, 4, 50257])

tensor([[[-1.2034, 0.3201, -0.7130, ..., -1.5548, -0.2390, -0.4667],

[-0.1192, 0.4539, -0.4432, ..., 0.2392, 1.3469, 1.2430],

[ 0.5307, 1.6720, -0.4695, ..., 1.1966, 0.0111, 0.5835],

[ 0.0139, 1.6754, -0.3388, ..., 1.1586, -0.0435, -1.0400]],

[[-1.0908, 0.1798, -0.9484, ..., -1.6047, 0.2439, -0.4530],

[-0.7860, 0.5581, -0.0610, ..., 0.4835, -0.0077, 1.6621],

[ 0.3567, 1.2698, -0.6398, ..., -0.0162, -0.1296, 0.3717],

[-0.2407, -0.7349, -0.5102, ..., 2.0057, -0.3694, 0.1814]]],

grad_fn=<UnsafeViewBackward0>)

Note

If you are running this code on Windows or Linux, the resulting values above may look like as follows:

Output shape: torch.Size([2, 4, 50257])

tensor([[[-0.9289, 0.2748, -0.7557, ..., -1.6070, 0.2702, -0.5888],

[-0.4476, 0.1726, 0.5354, ..., -0.3932, 1.5285, 0.8557],

[ 0.5680, 1.6053, -0.2155, ..., 1.1624, 0.1380, 0.7425],

[ 0.0447, 2.4787, -0.8843, ..., 1.3219, -0.0864, -0.5856]],

[[-1.5474, -0.0542, -1.0571, ..., -1.8061, -0.4494, -0.6747],

[-0.8422, 0.8243, -0.1098, ..., -0.1434, 0.2079, 1.2046],

[ 0.1355, 1.1858, -0.1453, ..., 0.0869, -0.1590, 0.1552],

[ 0.1666, -0.8138, 0.2307, ..., 2.5035, -0.3055, -0.3083]]],

grad_fn=<UnsafeViewBackward0>)

Since these are just random numbers, this is not a reason for concern, and you can proceed with the remainder of the chapter without issues

One possible reason for this discrepancy is the differing behavior of

nn.Dropoutacross operating systems, depending on how PyTorch was compiled, as discussed here on the PyTorch issue tracker

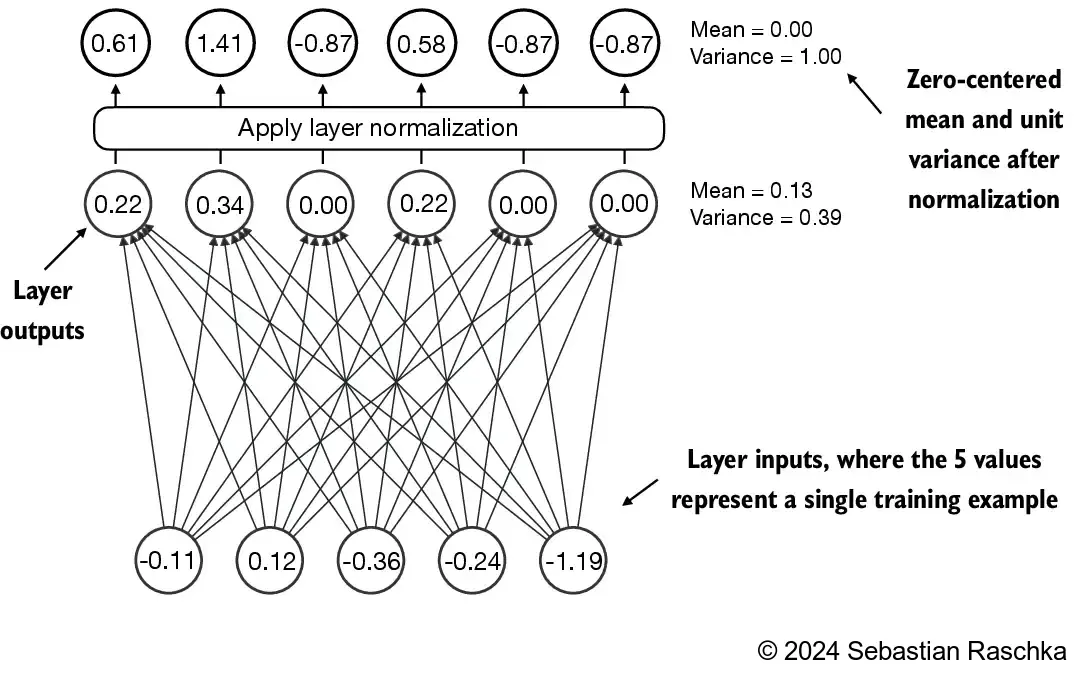

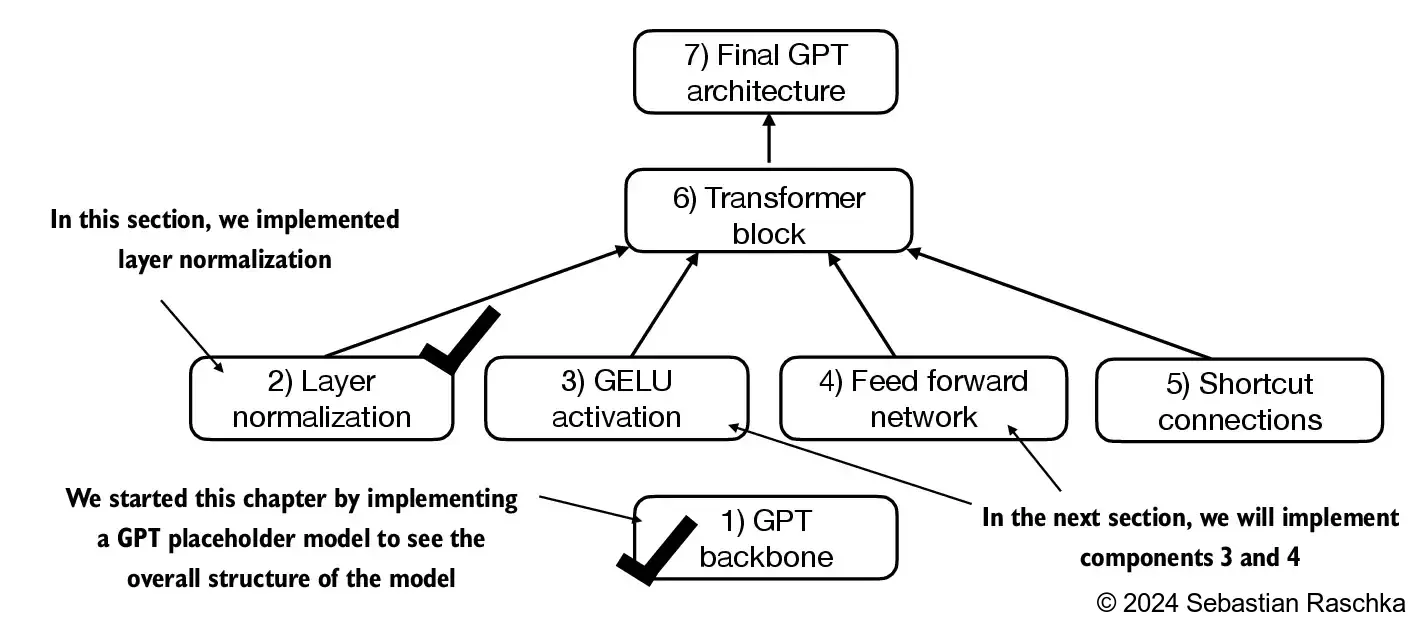

4.2 Normalizing activations with layer normalization#

Layer normalization, also known as LayerNorm (Ba et al. 2016), centers the activations of a neural network layer around a mean of 0 and normalizes their variance to 1

This stabilizes training and enables faster convergence to effective weights

Layer normalization is applied both before and after the multi-head attention module within the transformer block, which we will implement later; it’s also applied before the final output layer

Let’s see how layer normalization works by passing a small input sample through a simple neural network layer:

torch.manual_seed(123)

# create 2 training examples with 5 dimensions (features) each

batch_example = torch.randn(2, 5)

layer = nn.Sequential(nn.Linear(5, 6), nn.ReLU())

out = layer(batch_example)

print(out)

tensor([[0.2260, 0.3470, 0.0000, 0.2216, 0.0000, 0.0000],

[0.2133, 0.2394, 0.0000, 0.5198, 0.3297, 0.0000]],

grad_fn=<ReluBackward0>)

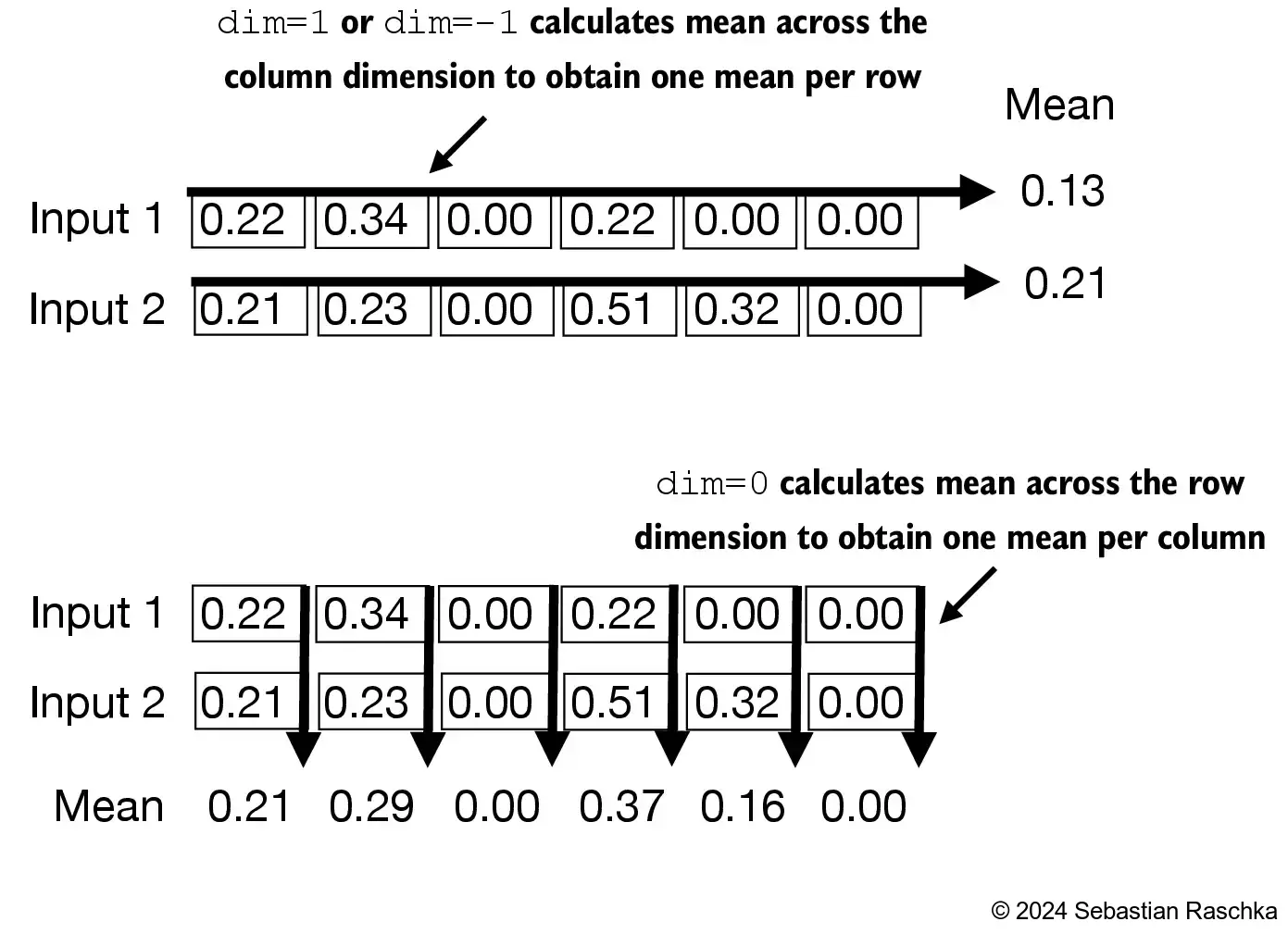

Let’s compute the mean and variance for each of the 2 inputs above:

mean = out.mean(dim=-1, keepdim=True)

var = out.var(dim=-1, keepdim=True)

print("Mean:\n", mean)

print("Variance:\n", var)

Mean:

tensor([[0.1324],

[0.2170]], grad_fn=<MeanBackward1>)

Variance:

tensor([[0.0231],

[0.0398]], grad_fn=<VarBackward0>)

The normalization is applied to each of the two inputs (rows) independently; using dim=-1 applies the calculation across the last dimension (in this case, the feature dimension) instead of the row dimension

Subtracting the mean and dividing by the square-root of the variance (standard deviation) centers the inputs to have a mean of 0 and a variance of 1 across the column (feature) dimension:

out_norm = (out - mean) / torch.sqrt(var)

print("Normalized layer outputs:\n", out_norm)

mean = out_norm.mean(dim=-1, keepdim=True)

var = out_norm.var(dim=-1, keepdim=True)

print("Mean:\n", mean)

print("Variance:\n", var)

Normalized layer outputs:

tensor([[ 0.6159, 1.4126, -0.8719, 0.5872, -0.8719, -0.8719],

[-0.0189, 0.1121, -1.0876, 1.5173, 0.5647, -1.0876]],

grad_fn=<DivBackward0>)

Mean:

tensor([[-5.9605e-08],

[ 1.9868e-08]], grad_fn=<MeanBackward1>)

Variance:

tensor([[1.0000],

[1.0000]], grad_fn=<VarBackward0>)

Each input is centered at 0 and has a unit variance of 1; to improve readability, we can disable PyTorch’s scientific notation:

torch.set_printoptions(sci_mode=False)

print("Mean:\n", mean)

print("Variance:\n", var)

Mean:

tensor([[ -0.0000],

[ 0.0000]], grad_fn=<MeanBackward1>)

Variance:

tensor([[1.0000],

[1.0000]], grad_fn=<VarBackward0>)

Above, we normalized the features of each input

Now, using the same idea, we can implement a

LayerNormclass:

class LayerNorm(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, emb_dim):

super().__init__()

self.eps = 1e-5

self.scale = nn.Parameter(torch.ones(emb_dim))

self.shift = nn.Parameter(torch.zeros(emb_dim))

def forward(self, x):

mean = x.mean(dim=-1, keepdim=True)

var = x.var(dim=-1, keepdim=True, unbiased=False)

norm_x = (x - mean) / torch.sqrt(var + self.eps)

return self.scale * norm_x + self.shift

Scale and shift

Note that in addition to performing the normalization by subtracting the mean and dividing by the variance, we added two trainable parameters, a

scaleand ashiftparameterThe initial

scale(multiplying by 1) andshift(adding 0) values don’t have any effect; however,scaleandshiftare trainable parameters that the LLM automatically adjusts during training if it is determined that doing so would improve the model’s performance on its training taskThis allows the model to learn appropriate scaling and shifting that best suit the data it is processing

Note that we also add a smaller value (

eps) before computing the square root of the variance; this is to avoid division-by-zero errors if the variance is 0

Biased variance

In the variance calculation above, setting

unbiased=Falsemeans using the formula \(\frac{\sum_i (x_i - \bar{x})^2}{n}\) to compute the variance where n is the sample size (here, the number of features or columns); this formula does not include Bessel’s correction (which usesn-1in the denominator), thus providing a biased estimate of the varianceFor LLMs, where the embedding dimension

nis very large, the difference between using n andn-1is negligibleHowever, GPT-2 was trained with a biased variance in the normalization layers, which is why we also adopted this setting for compatibility reasons with the pretrained weights that we will load in later chapters

Let’s now try out

LayerNormin practice:

ln = LayerNorm(emb_dim=5)

out_ln = ln(batch_example)

mean = out_ln.mean(dim=-1, keepdim=True)

var = out_ln.var(dim=-1, unbiased=False, keepdim=True)

print("Mean:\n", mean)

print("Variance:\n", var)

Mean:

tensor([[ -0.0000],

[ 0.0000]], grad_fn=<MeanBackward1>)

Variance:

tensor([[1.0000],

[1.0000]], grad_fn=<VarBackward0>)

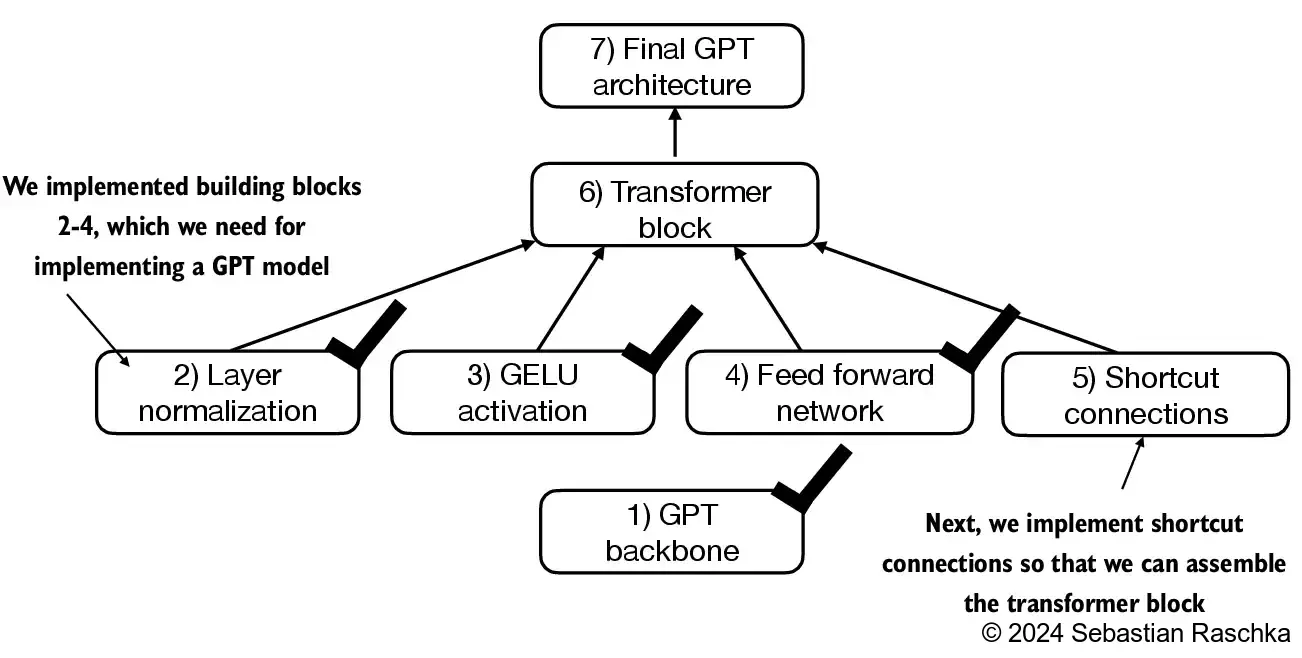

4.3 Implementing a feed forward network with GELU activations#

In this section, we implement a small neural network submodule that is used as part of the transformer block in LLMs

We start with the activation function

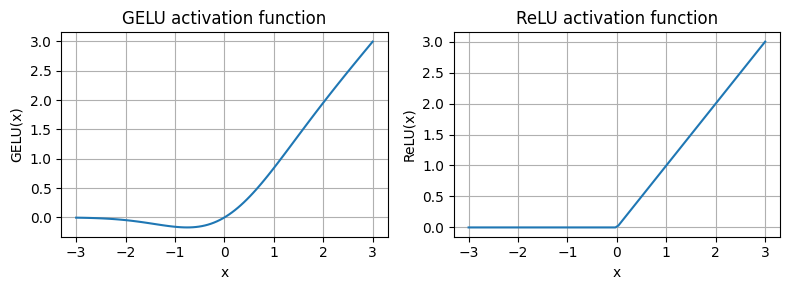

In deep learning, ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit) activation functions are commonly used due to their simplicity and effectiveness in various neural network architectures

In LLMs, various other types of activation functions are used beyond the traditional ReLU; two notable examples are GELU (Gaussian Error Linear Unit) and SwiGLU (Swish-Gated Linear Unit)

GELU and SwiGLU are more complex, smooth activation functions incorporating Gaussian and sigmoid-gated linear units, respectively, offering better performance for deep learning models, unlike the simpler, piecewise linear function of ReLU

GELU (Hendrycks and Gimpel 2016) can be implemented in several ways; the exact version is defined as GELU(x)=x⋅Φ(x), where Φ(x) is the cumulative distribution function of the standard Gaussian distribution.

In practice, it’s common to implement a computationally cheaper approximation: \(\text{GELU}(x) \approx 0.5 \cdot x \cdot \left(1 + \tanh\left[\sqrt{\frac{2}{\pi}} \cdot \left(x + 0.044715 \cdot x^3\right)\right]\right) \) (the original GPT-2 model was also trained with this approximation)

class GELU(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

def forward(self, x):

return 0.5 * x * (1 + torch.tanh(

torch.sqrt(torch.tensor(2.0 / torch.pi)) *

(x + 0.044715 * torch.pow(x, 3))

))

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

gelu, relu = GELU(), nn.ReLU()

# Some sample data

x = torch.linspace(-3, 3, 100)

y_gelu, y_relu = gelu(x), relu(x)

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 3))

for i, (y, label) in enumerate(zip([y_gelu, y_relu], ["GELU", "ReLU"]), 1):

plt.subplot(1, 2, i)

plt.plot(x, y)

plt.title(f"{label} activation function")

plt.xlabel("x")

plt.ylabel(f"{label}(x)")

plt.grid(True)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

As we can see, ReLU is a piecewise linear function that outputs the input directly if it is positive; otherwise, it outputs zero

GELU is a smooth, non-linear function that approximates ReLU but with a non-zero gradient for negative values (except at approximately -0.75)

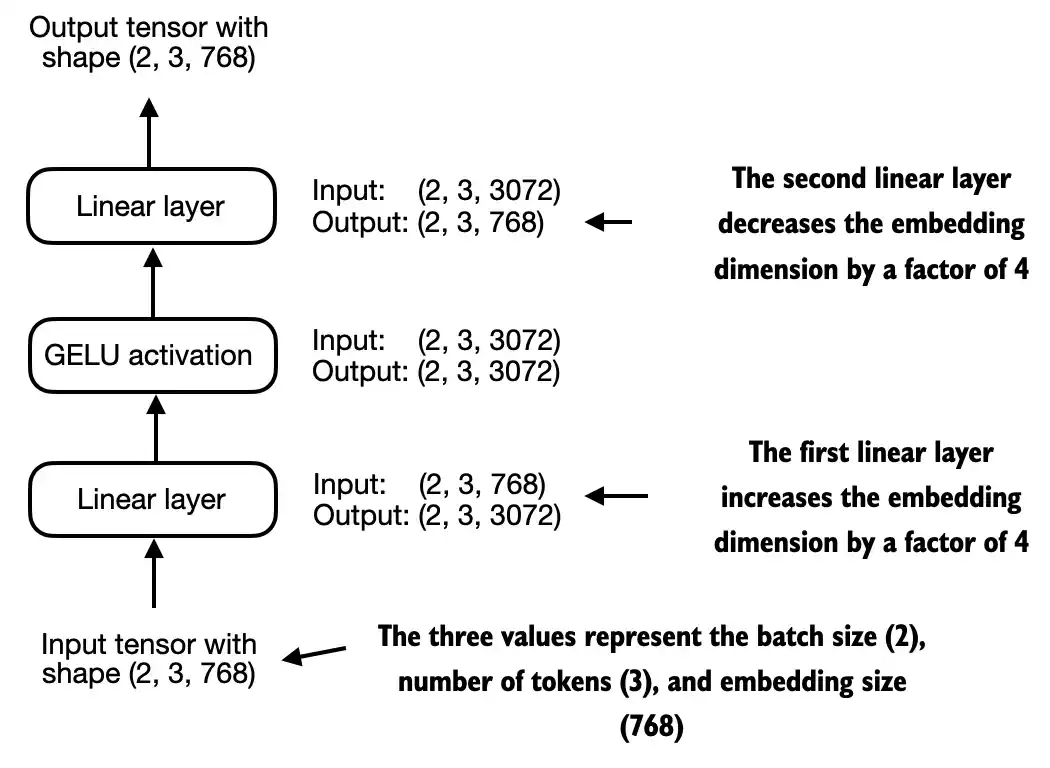

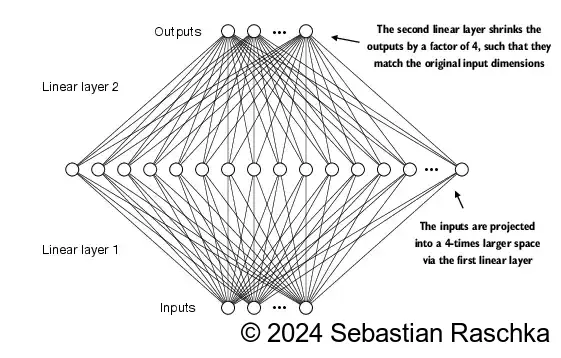

Next, let’s implement the small neural network module,

FeedForward, that we will be using in the LLM’s transformer block later:

class FeedForward(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, cfg):

super().__init__()

self.layers = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(cfg["emb_dim"], 4 * cfg["emb_dim"]),

GELU(),

nn.Linear(4 * cfg["emb_dim"], cfg["emb_dim"]),

)

def forward(self, x):

return self.layers(x)

print(GPT_CONFIG_124M["emb_dim"])

768

ffn = FeedForward(GPT_CONFIG_124M)

# input shape: [batch_size, num_token, emb_size]

x = torch.rand(2, 3, 768)

out = ffn(x)

print(out.shape)

torch.Size([2, 3, 768])

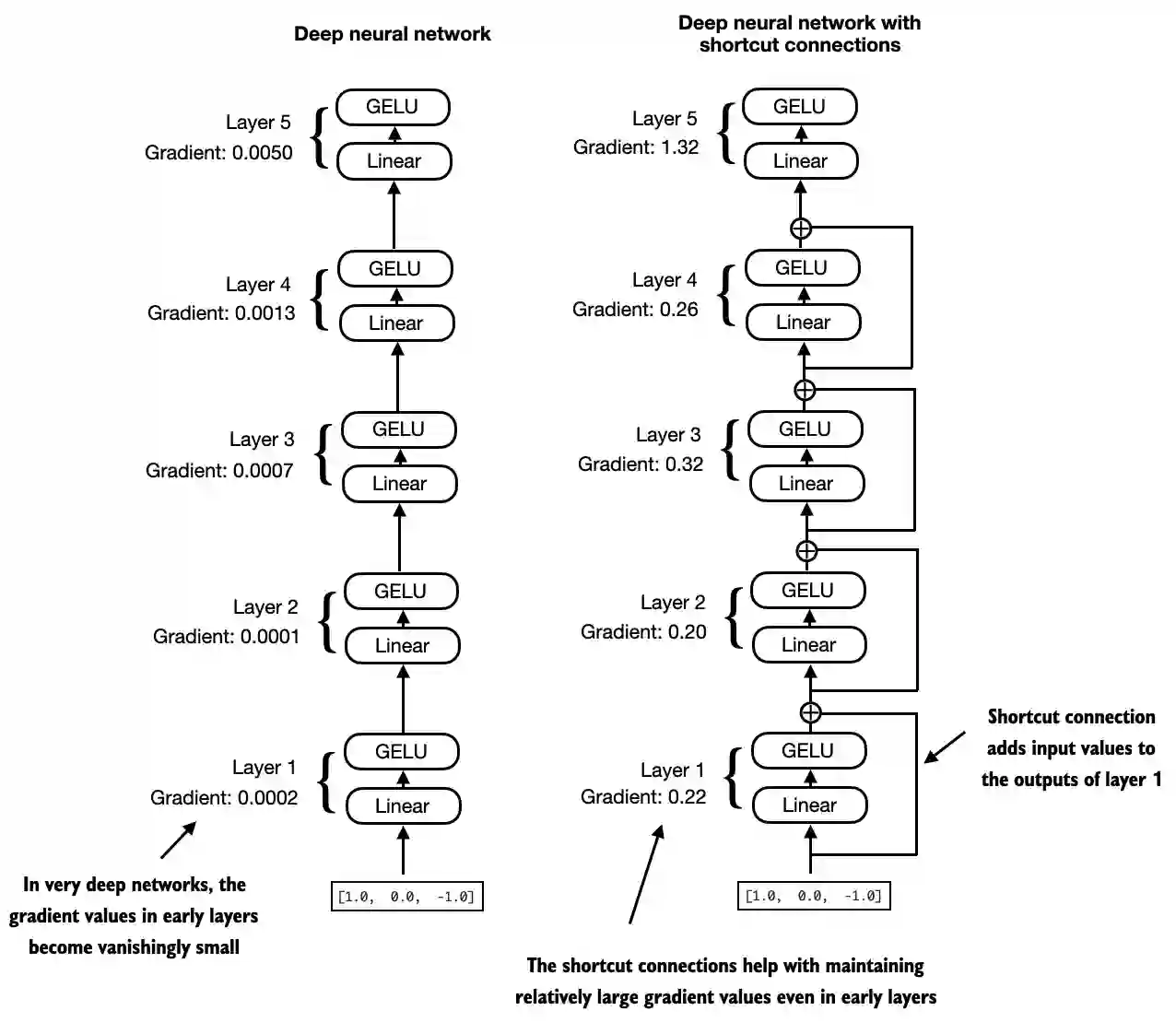

4.4 Adding shortcut connections#

Next, let’s talk about the concept behind shortcut connections, also called skip or residual connections

Originally, shortcut connections were proposed in deep networks for computer vision (residual networks) to mitigate vanishing gradient problems

A shortcut connection creates an alternative shorter path for the gradient to flow through the network

This is achieved by adding the output of one layer to the output of a later layer, usually skipping one or more layers in between

Let’s illustrate this idea with a small example network:

In code, it looks like this:

class ExampleDeepNeuralNetwork(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, layer_sizes, use_shortcut):

super().__init__()

self.use_shortcut = use_shortcut

self.layers = nn.ModuleList([

nn.Sequential(nn.Linear(layer_sizes[0], layer_sizes[1]), GELU()),

nn.Sequential(nn.Linear(layer_sizes[1], layer_sizes[2]), GELU()),

nn.Sequential(nn.Linear(layer_sizes[2], layer_sizes[3]), GELU()),

nn.Sequential(nn.Linear(layer_sizes[3], layer_sizes[4]), GELU()),

nn.Sequential(nn.Linear(layer_sizes[4], layer_sizes[5]), GELU())

])

def forward(self, x):

for layer in self.layers:

# Compute the output of the current layer

layer_output = layer(x)

# Check if shortcut can be applied

if self.use_shortcut and x.shape == layer_output.shape:

x = x + layer_output

else:

x = layer_output

return x

def print_gradients(model, x):

# Forward pass

output = model(x)

target = torch.tensor([[0.]])

# Calculate loss based on how close the target

# and output are

loss = nn.MSELoss()

loss = loss(output, target)

# Backward pass to calculate the gradients

loss.backward()

for name, param in model.named_parameters():

if 'weight' in name:

# Print the mean absolute gradient of the weights

print(f"{name} has gradient mean of {param.grad.abs().mean().item()}")

Let’s print the gradient values first without shortcut connections:

layer_sizes = [3, 3, 3, 3, 3, 1]

sample_input = torch.tensor([[1., 0., -1.]])

torch.manual_seed(123)

model_without_shortcut = ExampleDeepNeuralNetwork(

layer_sizes, use_shortcut=False

)

print_gradients(model_without_shortcut, sample_input)

layers.0.0.weight has gradient mean of 0.00020173587836325169

layers.1.0.weight has gradient mean of 0.00012011159560643137

layers.2.0.weight has gradient mean of 0.0007152039906941354

layers.3.0.weight has gradient mean of 0.0013988736318424344

layers.4.0.weight has gradient mean of 0.005049645435065031

Next, let’s print the gradient values with shortcut connections:

torch.manual_seed(123)

model_with_shortcut = ExampleDeepNeuralNetwork(

layer_sizes, use_shortcut=True

)

print_gradients(model_with_shortcut, sample_input)

layers.0.0.weight has gradient mean of 0.22169792652130127

layers.1.0.weight has gradient mean of 0.20694106817245483

layers.2.0.weight has gradient mean of 0.32896995544433594

layers.3.0.weight has gradient mean of 0.2665732204914093

layers.4.0.weight has gradient mean of 1.3258540630340576

As we can see based on the output above, shortcut connections prevent the gradients from vanishing in the early layers (towards

layer.0)We will use this concept of a shortcut connection next when we implement a transformer block

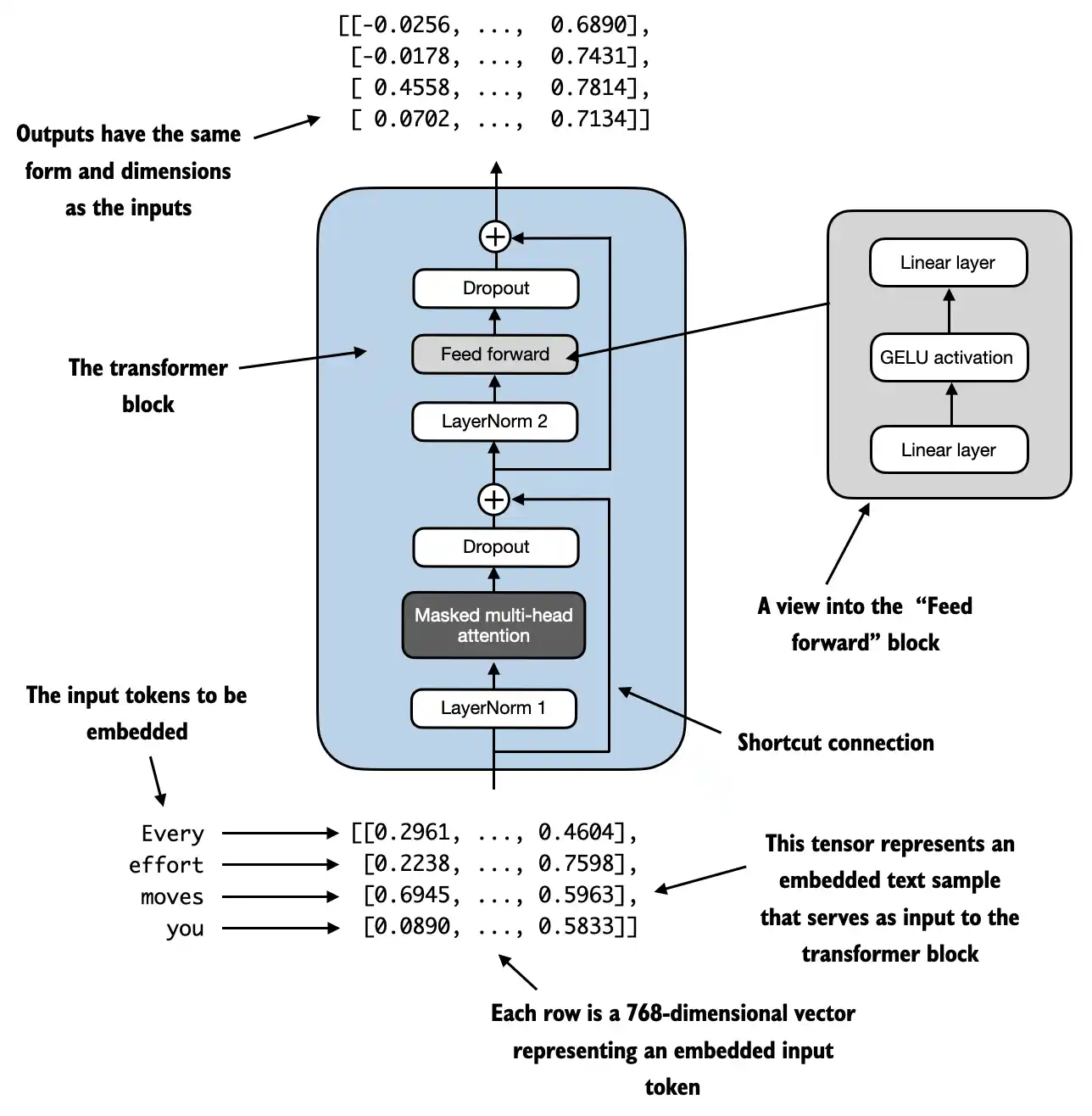

4.5 Connecting attention and linear layers in a transformer block#

In this section, we now combine the previous concepts into a so-called transformer block

A transformer block combines the causal multi-head attention module from the previous chapter with the linear layers, the feed forward neural network we implemented in an earlier section

In addition, the transformer block also uses dropout and shortcut connections

# If the `previous_chapters.py` file is not available locally,

# you can import it from the `llms-from-scratch` PyPI package.

# For details, see: https://github.com/rasbt/LLMs-from-scratch/tree/main/pkg

# E.g.,

# from llms_from_scratch.ch03 import MultiHeadAttention

from previous_chapters import MultiHeadAttention

class TransformerBlock(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, cfg):

super().__init__()

self.att = MultiHeadAttention(

d_in=cfg["emb_dim"],

d_out=cfg["emb_dim"],

context_length=cfg["context_length"],

num_heads=cfg["n_heads"],

dropout=cfg["drop_rate"],

qkv_bias=cfg["qkv_bias"])

self.ff = FeedForward(cfg)

self.norm1 = LayerNorm(cfg["emb_dim"])

self.norm2 = LayerNorm(cfg["emb_dim"])

self.drop_shortcut = nn.Dropout(cfg["drop_rate"])

def forward(self, x):

# Shortcut connection for attention block

shortcut = x

x = self.norm1(x)

x = self.att(x) # Shape [batch_size, num_tokens, emb_size]

x = self.drop_shortcut(x)

x = x + shortcut # Add the original input back

# Shortcut connection for feed forward block

shortcut = x

x = self.norm2(x)

x = self.ff(x)

x = self.drop_shortcut(x)

x = x + shortcut # Add the original input back

return x

Suppose we have 2 input samples with 6 tokens each, where each token is a 768-dimensional embedding vector; then this transformer block applies self-attention, followed by linear layers, to produce an output of similar size

You can think of the output as an augmented version of the context vectors we discussed in the previous chapter

torch.manual_seed(123)

x = torch.rand(2, 4, 768) # Shape: [batch_size, num_tokens, emb_dim]

block = TransformerBlock(GPT_CONFIG_124M)

output = block(x)

print("Input shape:", x.shape)

print("Output shape:", output.shape)

Input shape: torch.Size([2, 4, 768])

Output shape: torch.Size([2, 4, 768])

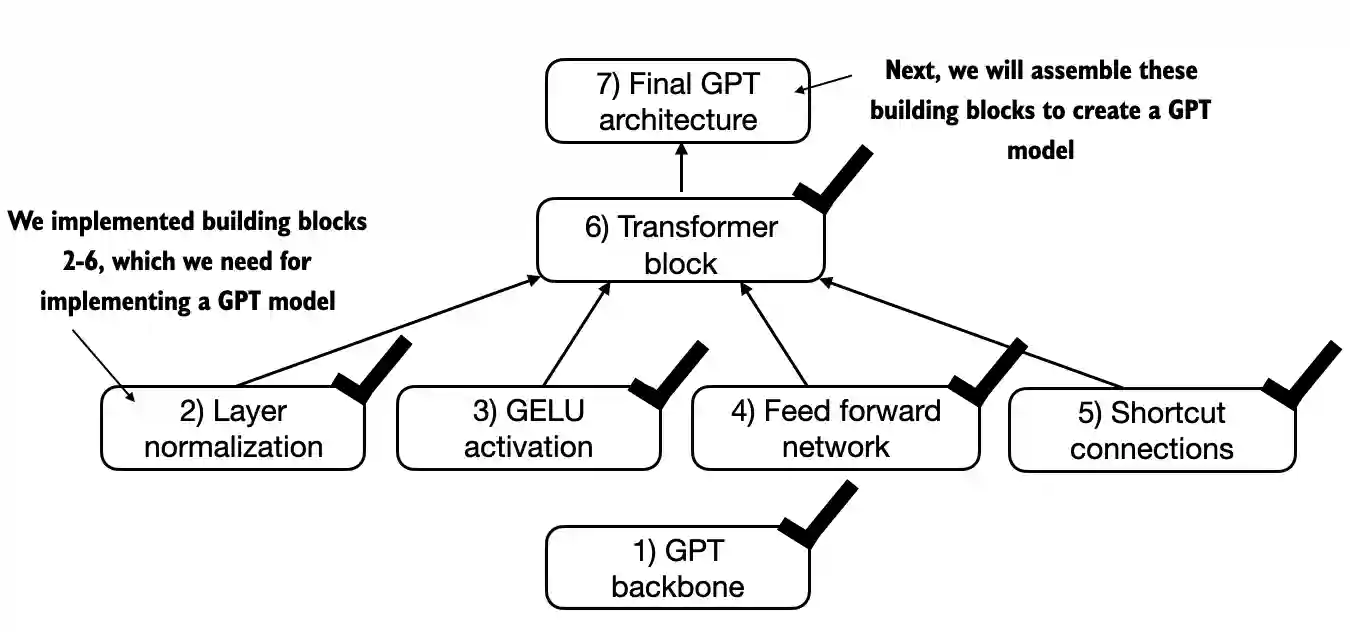

4.6 Coding the GPT model#

We are almost there: now let’s plug in the transformer block into the architecture we coded at the very beginning of this chapter so that we obtain a usable GPT architecture

Note that the transformer block is repeated multiple times; in the case of the smallest 124M GPT-2 model, we repeat it 12 times:

The corresponding code implementation, where

cfg["n_layers"] = 12:

class GPTModel(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, cfg):

super().__init__()

self.tok_emb = nn.Embedding(cfg["vocab_size"], cfg["emb_dim"])

self.pos_emb = nn.Embedding(cfg["context_length"], cfg["emb_dim"])

self.drop_emb = nn.Dropout(cfg["drop_rate"])

self.trf_blocks = nn.Sequential(

*[TransformerBlock(cfg) for _ in range(cfg["n_layers"])])

self.final_norm = LayerNorm(cfg["emb_dim"])

self.out_head = nn.Linear(

cfg["emb_dim"], cfg["vocab_size"], bias=False

)

def forward(self, in_idx):

batch_size, seq_len = in_idx.shape

tok_embeds = self.tok_emb(in_idx)

pos_embeds = self.pos_emb(torch.arange(seq_len, device=in_idx.device))

x = tok_embeds + pos_embeds # Shape [batch_size, num_tokens, emb_size]

x = self.drop_emb(x)

x = self.trf_blocks(x)

x = self.final_norm(x)

logits = self.out_head(x)

return logits

Using the configuration of the 124M parameter model, we can now instantiate this GPT model with random initial weights as follows:

torch.manual_seed(123)

model = GPTModel(GPT_CONFIG_124M)

out = model(batch)

print("Input batch:\n", batch)

print("\nOutput shape:", out.shape)

print(out)

Input batch:

tensor([[6109, 3626, 6100, 345],

[6109, 1110, 6622, 257]])

Output shape: torch.Size([2, 4, 50257])

tensor([[[ 0.3613, 0.4222, -0.0711, ..., 0.3483, 0.4661, -0.2838],

[-0.1792, -0.5660, -0.9485, ..., 0.0477, 0.5181, -0.3168],

[ 0.7120, 0.0332, 0.1085, ..., 0.1018, -0.4327, -0.2553],

[-1.0076, 0.3418, -0.1190, ..., 0.7195, 0.4023, 0.0532]],

[[-0.2564, 0.0900, 0.0335, ..., 0.2659, 0.4454, -0.6806],

[ 0.1230, 0.3653, -0.2074, ..., 0.7705, 0.2710, 0.2246],

[ 1.0558, 1.0318, -0.2800, ..., 0.6936, 0.3205, -0.3178],

[-0.1565, 0.3926, 0.3288, ..., 1.2630, -0.1858, 0.0388]]],

grad_fn=<UnsafeViewBackward0>)

We will train this model in the next chapter

However, a quick note about its size: we previously referred to it as a 124M parameter model; we can double check this number as follows:

total_params = sum(p.numel() for p in model.parameters())

print(f"Total number of parameters: {total_params:,}")

Total number of parameters: 163,009,536

As we see above, this model has 163M, not 124M parameters; why?

In the original GPT-2 paper, the researchers applied weight tying, which means that they reused the token embedding layer (

tok_emb) as the output layer, which means settingself.out_head.weight = self.tok_emb.weightThe token embedding layer projects the 50,257-dimensional one-hot encoded input tokens to a 768-dimensional embedding representation

The output layer projects 768-dimensional embeddings back into a 50,257-dimensional representation so that we can convert these back into words (more about that in the next section)

So, the embedding and output layer have the same number of weight parameters, as we can see based on the shape of their weight matrices

However, a quick note about its size: we previously referred to it as a 124M parameter model; we can double check this number as follows:

print("Token embedding layer shape:", model.tok_emb.weight.shape)

print("Output layer shape:", model.out_head.weight.shape)

Token embedding layer shape: torch.Size([50257, 768])

Output layer shape: torch.Size([50257, 768])

In the original GPT-2 paper, the researchers reused the token embedding matrix as an output matrix

Correspondingly, if we subtracted the number of parameters of the output layer, we’d get a 124M parameter model:

total_params_gpt2 = total_params - sum(p.numel() for p in model.out_head.parameters())

print(f"Number of trainable parameters considering weight tying: {total_params_gpt2:,}")

Number of trainable parameters considering weight tying: 124,412,160

In practice, I found it easier to train the model without weight-tying, which is why we didn’t implement it here

However, we will revisit and apply this weight-tying idea later when we load the pretrained weights in chapter 5

Lastly, we can compute the memory requirements of the model as follows, which can be a helpful reference point:

# Calculate the total size in bytes (assuming float32, 4 bytes per parameter)

total_size_bytes = total_params * 4

# Convert to megabytes

total_size_mb = total_size_bytes / (1024 * 1024)

print(f"Total size of the model: {total_size_mb:.2f} MB")

Total size of the model: 621.83 MB

Exercise: you can try the following other configurations, which are referenced in the GPT-2 paper, as well.

GPT2-small (the 124M configuration we already implemented):

“emb_dim” = 768

“n_layers” = 12

“n_heads” = 12

GPT2-medium:

“emb_dim” = 1024

“n_layers” = 24

“n_heads” = 16

GPT2-large:

“emb_dim” = 1280

“n_layers” = 36

“n_heads” = 20

GPT2-XL:

“emb_dim” = 1600

“n_layers” = 48

“n_heads” = 25

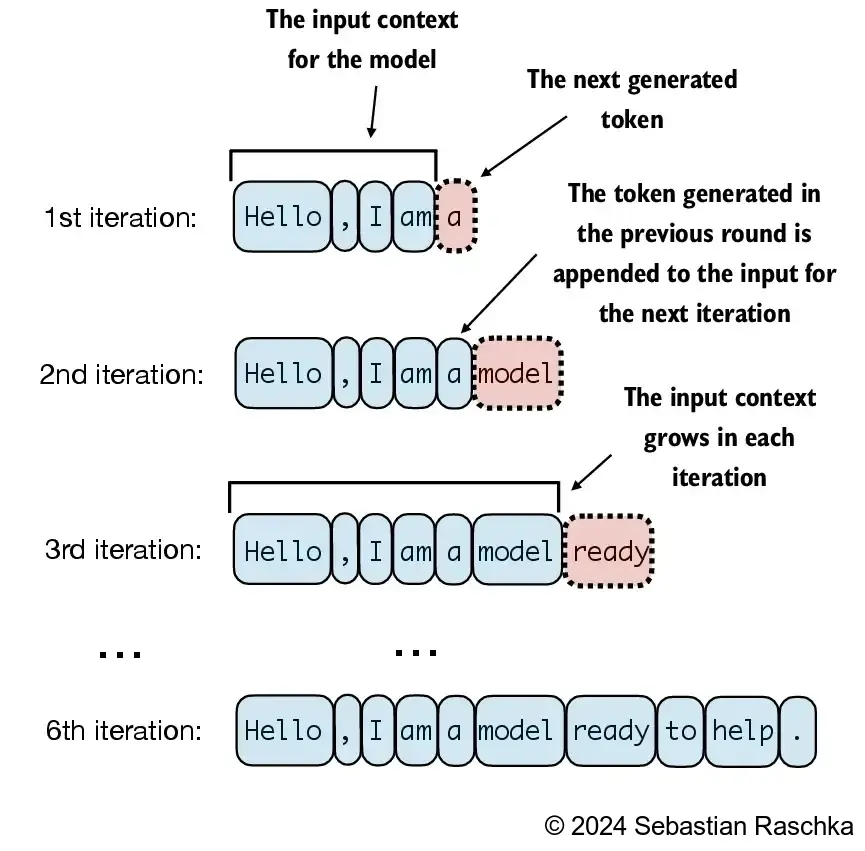

4.7 Generating text#

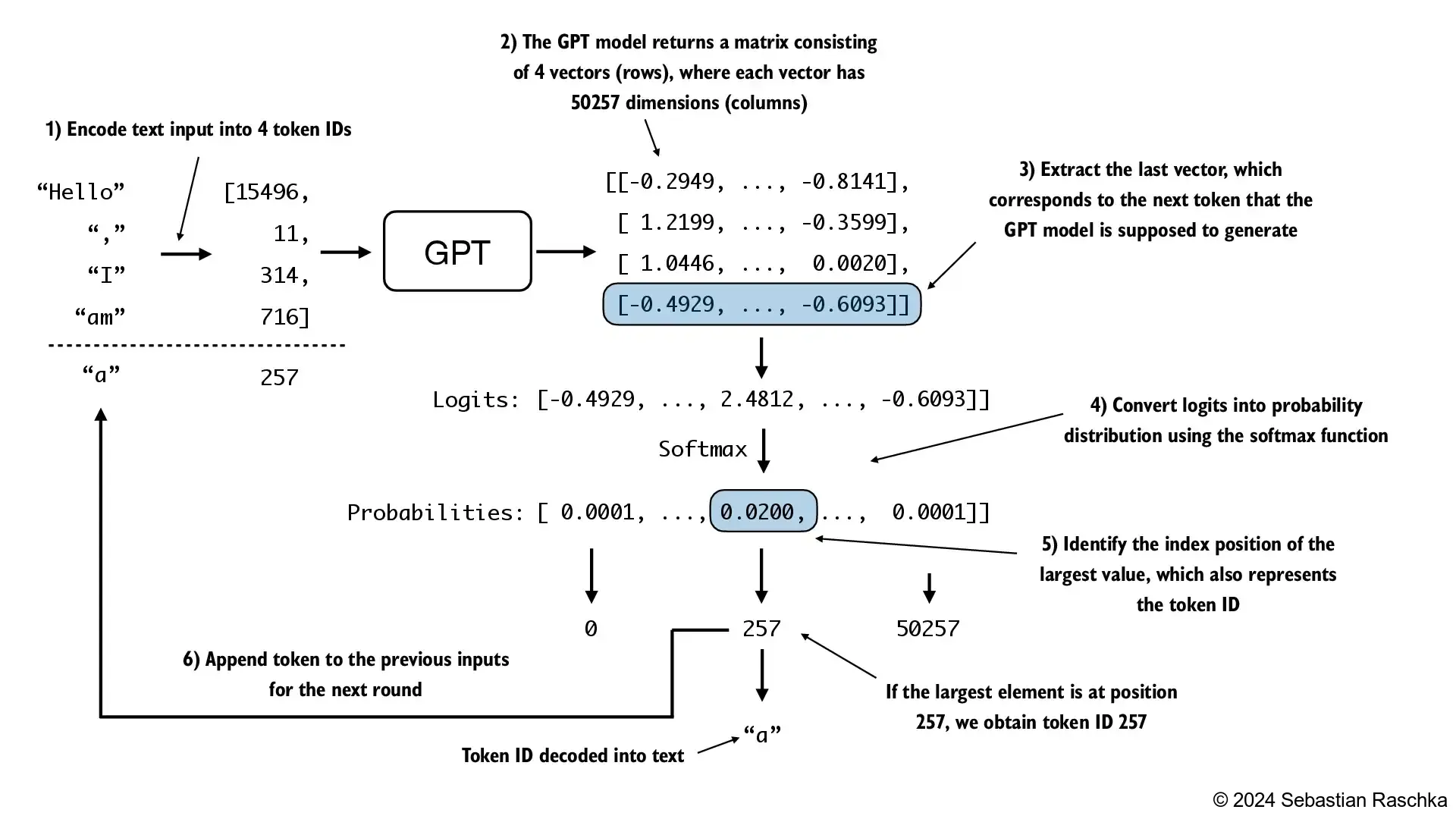

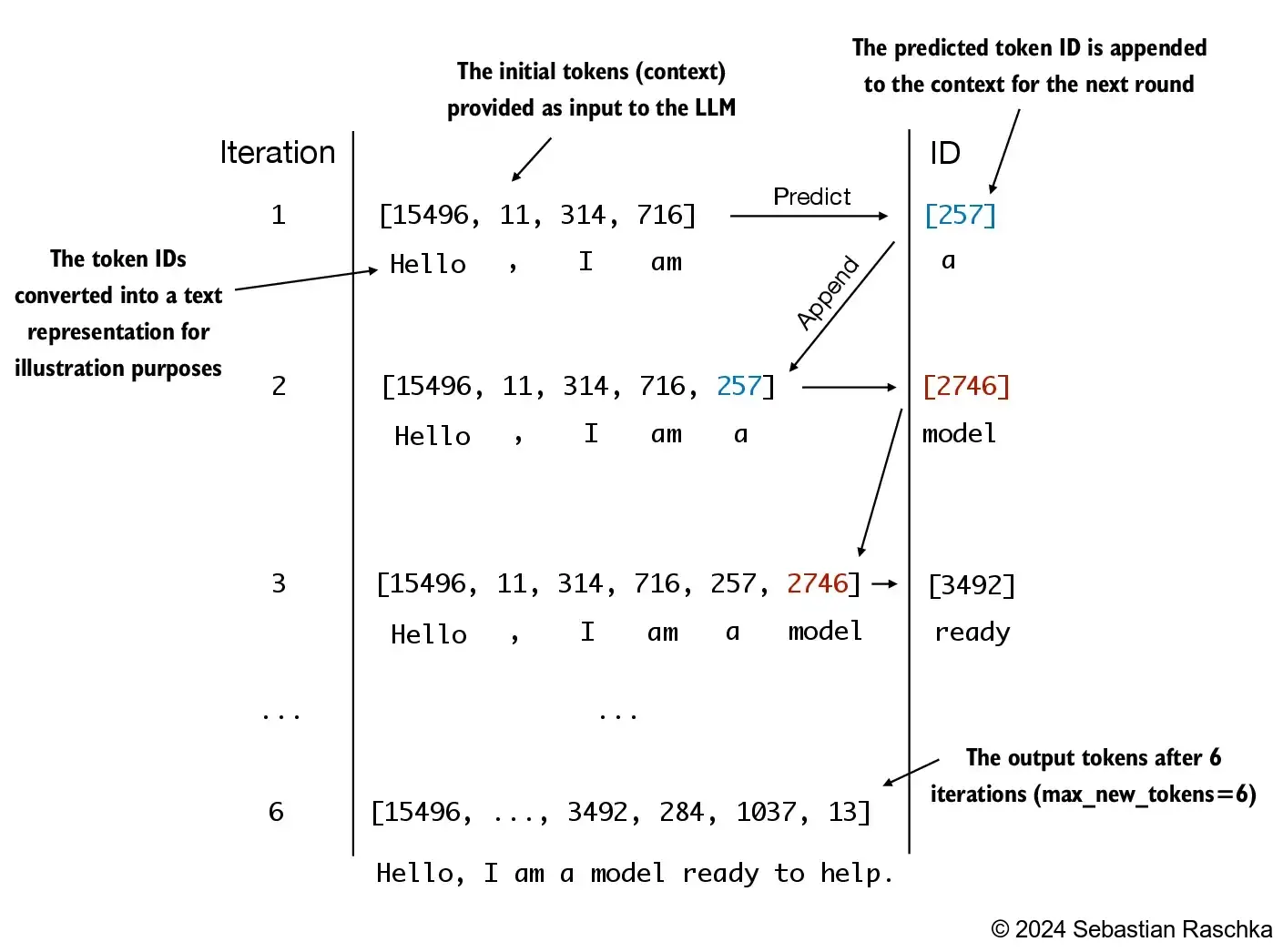

LLMs like the GPT model we implemented above are used to generate one word at a time

The following

generate_text_simplefunction implements greedy decoding, which is a simple and fast method to generate textIn greedy decoding, at each step, the model chooses the word (or token) with the highest probability as its next output (the highest logit corresponds to the highest probability, so we technically wouldn’t even have to compute the softmax function explicitly)

In the next chapter, we will implement a more advanced

generate_textfunctionThe figure below depicts how the GPT model, given an input context, generates the next word token

def generate_text_simple(model, idx, max_new_tokens, context_size):

# idx is (batch, n_tokens) array of indices in the current context

for _ in range(max_new_tokens):

# Crop current context if it exceeds the supported context size

# E.g., if LLM supports only 5 tokens, and the context size is 10

# then only the last 5 tokens are used as context

idx_cond = idx[:, -context_size:]

# Get the predictions

with torch.no_grad():

logits = model(idx_cond)

# Focus only on the last time step

# (batch, n_tokens, vocab_size) becomes (batch, vocab_size)

logits = logits[:, -1, :]

# Apply softmax to get probabilities

probas = torch.softmax(logits, dim=-1) # (batch, vocab_size)

# Get the idx of the vocab entry with the highest probability value

idx_next = torch.argmax(probas, dim=-1, keepdim=True) # (batch, 1)

# Append sampled index to the running sequence

idx = torch.cat((idx, idx_next), dim=1) # (batch, n_tokens+1)

return idx

The

generate_text_simpleabove implements an iterative process, where it creates one token at a time

Let’s prepare an input example:

start_context = "Hello, I am"

encoded = tokenizer.encode(start_context)

print("encoded:", encoded)

encoded_tensor = torch.tensor(encoded).unsqueeze(0)

print("encoded_tensor.shape:", encoded_tensor.shape)

encoded: [15496, 11, 314, 716]

encoded_tensor.shape: torch.Size([1, 4])

model.eval() # disable dropout

out = generate_text_simple(

model=model,

idx=encoded_tensor,

max_new_tokens=6,

context_size=GPT_CONFIG_124M["context_length"]

)

print("Output:", out)

print("Output length:", len(out[0]))

Output: tensor([[15496, 11, 314, 716, 27018, 24086, 47843, 30961, 42348, 7267]])

Output length: 10

Remove batch dimension and convert back into text:

decoded_text = tokenizer.decode(out.squeeze(0).tolist())

print(decoded_text)

Hello, I am Featureiman Byeswickattribute argue

Note that the model is untrained; hence the random output texts above

We will train the model in the next chapter

Summary and takeaways#

See the ./gpt.py script, a self-contained script containing the GPT model we implement in this Jupyter notebook

You can find the exercise solutions in ./exercise-solutions.ipynb